Musicians Daniel Heffez (saxophone), Daniel Fabricant (bass), and Bob Brumbeloe (guitar) play in Golden Gate Park after hearing a gig had been cancelled but before the Bay are was effectively put in lockdown. Credit: Basem Moussa

When musician Patrick Jeffords (Toro y Moi, Kid Trails) learned that all of his upcoming shows were cancelled and that The Hatch, the Oakland bar where Jeffords works, had to close to help stop the spread of the novel coronavirus, he got a little nervous. “In a way, being home has been kind of fun so far — playing music, watching movies — but then I’m like, ‘Oh, I’m not going to be able to work for a month at least,’” he says.

At the urge of The Hatch owners, the musician promptly filed for unemployment — along with nearly 300,000 other Californians — and began work on a song with his partner Charlotte Hacker-Mullen (Sludge Pony), a musician and visual artist in the Bay Area.

“Pandemic” captures this moment in time and will hopefully raise a little money for the duo while they’re both out of work. “So far, we’ve gotten about $200 from the song’s sales so — that’s groceries,” says Jeffords. A lot of artists are in a similarly bleak situation.

In an effort to help some of the musicians who are now out of work for the foreseeable future, Oakland-based steaming service Bandcamp pledged to not take their typical 15 percent cut from any music bought on March 20, saying in an email to subscribers: “If you are able, please join us in putting some much needed money directly into artists’ pockets.” It’s a nice nod of support to musicians globally who can no longer tour or, often, even practice.

Music sales are helpful but certainly not enough to keep many artists afloat. “When people’s main source of income is completely cut off, where do we go, and who fills that space?” asks San Francisco musician Luke Sweeney. A father of two, Sweeney and his wife Rohini Moradi co-own The Cocktail Camp, a bartender training school in San Francisco that had to close down due to the virus. The school is offering online courses and reduced rates, but the future is nerve-wracking.

Musician Luke Sweeney in the storage room of his San Francisco apartment.

“I’m willing to work, but there’s just not much we can do right now. Some bandmates are 9-to-5ers and have offered to help financially and have actually stepped up to do so. Meanwhile, we're selling off some baby stuff. I put my tour van up for sale. Definitely scrambling to make ends meet,” he says.

An appeal to local governments

This type of predicament is why Dr. Rupa Marya started a petition to San Francisco Mayor London Breed and Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf, requesting not only a moratorium on evictions — California Governor Gavin Newsom has since issued an executive order to prevent evictions throughout the state — but asking both cities to “enact a plan to forgive rent for wage workers who will be unable to make the income needed to pay rent for the month of April,” read the petition.

As a physician and associate professor of medicine at UCSF and a musician in the band Rupa and the April Fishes, Marya is concerned about needless deaths. “This is a really important time to think about how, as our economy is grinding to a halt, the people most vulnerable will be wage workers,” she says. “People will be losing their health insurance. I’m really worried about the fallout.” The petition has received more than 9,000 signatures so far and has many artists feeling hopeful yet anxious.

“What I’m worried about is: What would happen if we don’t pay right now?” asks Ginger Fierstein, a Berkeley-based photographer well known in the music scene for her portraits and experimental photography. Fierstein also tends bar and works at Photolab in Berkeley to help pay the bills. “I would like more communication from our city, saying specifically and in great detail, ‘Here’s what will happen for renters’ — and with assurances that not paying this month won’t negatively affect my legal standing in the house,” she says. Fierstein wonders, too, what will happen to her landlord and the effects on other homeowners who won’t receive income from their renters.

“I feel very privileged that I was able to save up a little nest egg,” shares Oakland hairstylist Hannah Skelton, who’s worked in San Francisco for years in support of her music projects, Cassiopeia and Abracadabra. After her salon closed for the foreseeable future, Skelton sent an email to her clients, sharing that she’d be giving online tutorials for how to trim your own hair these next few weeks and suggesting clients prepay for their next visit. She’s aware that those pre-paid cuts will mean that those customers won’t be paying at the date that they actually come in for their service, but she needs rent now. She’s not willing to put herself or the public at risk by continuing to offer cuts.

At loose ends

So, what are other artists doing to make the bills and pass the time? “At first, I thought, well at least I can practice,” shared Oakland musician and instructor Jordan Glenn (BEAK, Sifter). Up until this week, Glenn had been playing numerous shows every month, teaching three days a week at San Francisco Rock Project, and heading a monthly showcase at Temescal Arts Center.

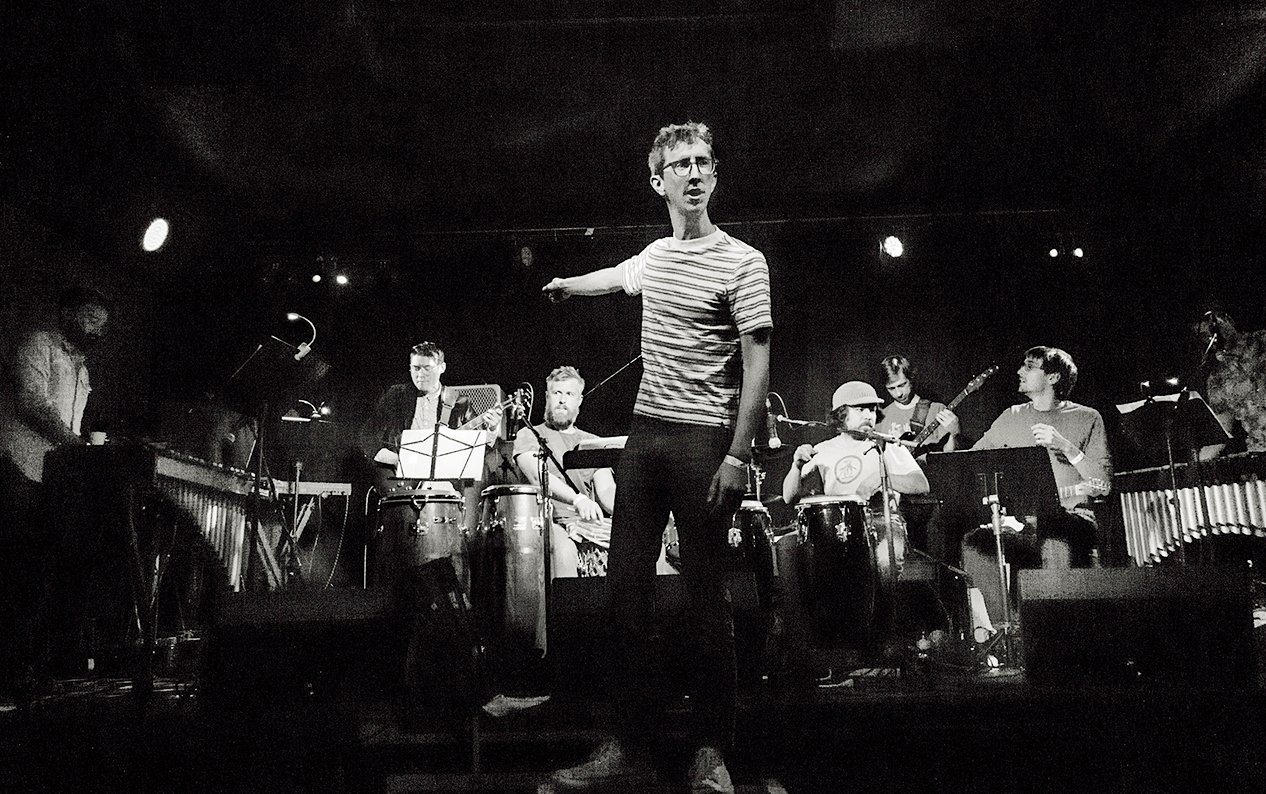

Musician Jordan Glenn instructs his band BEAK. Credit: Lenny Gonzalez

When we spoke to him, he was on his way home from the space he uses to practice, explaining that they’d shut down but that at least he was able to pick up his drums. “Not that I can really practice those at home,” he says with a quiet laugh. Glenn hopes that people will buy more music digitally, purchase merchandise, and schedule online classes.

It’s difficult to teach an online music course, though, not just because of the lag, but the experience. “Being in a room with other people is a huge part of what we do. So, we can’t even play with other people right now if we wanted to,” says Glenn.

When Dr. Marya started the letter to the mayors, it was with this concept in mind. “If we’re saying you can’t gather, we’re saying you can’t make a living,” she explains. “Many of my friends are musicians, and most of them don’t have a nest egg or great health insurance, so I created this letter.”

Marya hopes to protect people whose incomes aren’t salaried. “People who do make salaries should still be paying their domestic workers, their gardeners. If your income isn’t affected by this, you should continue supporting your staff,” she urges.

The political winds blow leftward

Marya isn’t shy about her support of Bernie Sanders, either. In fact, it’s a name that comes up with a lot of artists and wage workers right now.

Sweeney stressed some of the same sentiments as Marya. “It’s easy for people to write off what Bernie’s saying as radical or whatnot,” he says, “but when he’s talking about changes to healthcare and support of the working class, we’re talking about basic services and needs that we are already paying our tax dollars for — it’s what he’s been saying this whole time. You have these super billionaires that are protected from all this — supposedly — but you have a vast number of people who can’t pay their rent.”

“Our current system just doesn’t protect everyone.”

The situation we’re in with COVID-19 is a warning sign of more to come, say many artists and advocates. “If we can bail Wall Street out, we should be able to bail out our healthcare system,” says Marya. “And the blessing of this virus is that it’s getting us to think about this collectively, offering us the opportunity to imagine a social contract that is different, where we look out for each other during this kind of threat. Our current system just doesn’t protect everyone.”

There’s a collective feeling among the artistic community that now is the time to stick together and remind fellow artists that although they may not be able to gather physically, they can gather virtually, because they must, in some form, gather. “I 100 percent support that petition,” says Hacker-Mullen, whose murals can be seen all over the Bay Area. She tends bar in San Francisco to help pay the rent and support her art. But now? “A large source of my income is completely cut off indefinitely. I don't really know how I’ll pay my rent — stay with family? A different career path? I just can’t afford rent right now,” Hacker-Mullen says.

Musician and artist Charlotte Hacker-Mullen in front of one of her many murals.

But asking artists to give up their livelihood is a grim alternative in a time when many people are looking to art. What do people do when they’re sad, confused, happy, exhilarated, mourning, celebrating? They listen to music. They watch films. They visit museums (virtually nowadays). So while artists throughout the country collectively ask for help from supporters and from the government during this time of uncertainty, all they can do is keep creating and pressing for support. As Dr. Marya argued, “If we don’t get what we need, we have to keep pushing. This is too crucial to give up on, too critical — our push needs to happen right now.”