“There’s a tendency to think that 3-D is best used for spectacle,” Eric Kurland tells me as we stand next to a display of vintage View-Masters. “People say, ‘Well, you wouldn’t use it for My Dinner with Andre.’ But I would argue that one of the things 3-D really excels at is creating a heightened sense of intimacy.”

Kurland would know about intimate — 3-D Space, his basement gallery in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Echo Park, is exactly that. In the small space he considers his “starter museum,” he occasionally holds open gallery hours. More often than not, however, he shows exhibits by appointment so he can get to know what people already understand about the history, science, and art of 3-D technology — and then fill them in on what they might not. Like me, for example, who arrived thinking that 3-D was best used for spectacle. Fast & Furious 7, Kung-Fu Panda 12, and Final Destination 24 all came to mind.

To counter my common misconception, Kurland offered the examples of One More Time With Feeling, a beautiful 3-D film chronicling musician Nick Cave as he records an album in the wake of his teenage son’s tragic death, and Wim Wender’s Oscar-nominated Pina, an emotionally visceral 3-D memorial to the late dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch. In fact, Wenders, who has since moved on to use 3-D for narrative film, publicly lamented to The Huffington Post about the “huge prejudice against one of the greatest inventions in the history of cinema.”

I realized I’d held that prejudice. The term “3-D” had become static to me — forever married to creatures from black lagoons, Victorian stereoscopes, or IMAX films about pandas and comic books. Don’t get me wrong — these are all things I deeply appreciate, but they always felt more like cool curiosities rather than an art form brimming with potential. “A friend of mine describes flat movies as ‘converting the real world into 2-D,’” Kurland says.

"VR that’s really effective, that really gives you the sensation of being immersed, is stereoscopic."

I get that, but 3-D isn’t like virtual reality — VR is the future, rich with possibility! Right? Kurland answers me patiently, as he has done others so many times before.

“Yeah, but the VR that’s really effective, that really gives you the sensation of being immersed, is stereoscopic,” he says, gently reminding me that VR is the experience, and it’s 3-D technology (along with 360-degree video, sound design, etc.) that makes it feel real. Kurland then references Morton Hellig’s Sensorama, a mechanical VR experiment from 1962 that displayed five short 3-D film “experiences,” simultaneously engaging sight, sound, smell, and touch.

It was at this point that I admitted I knew nothing and let Kurland take over.

Origin stories

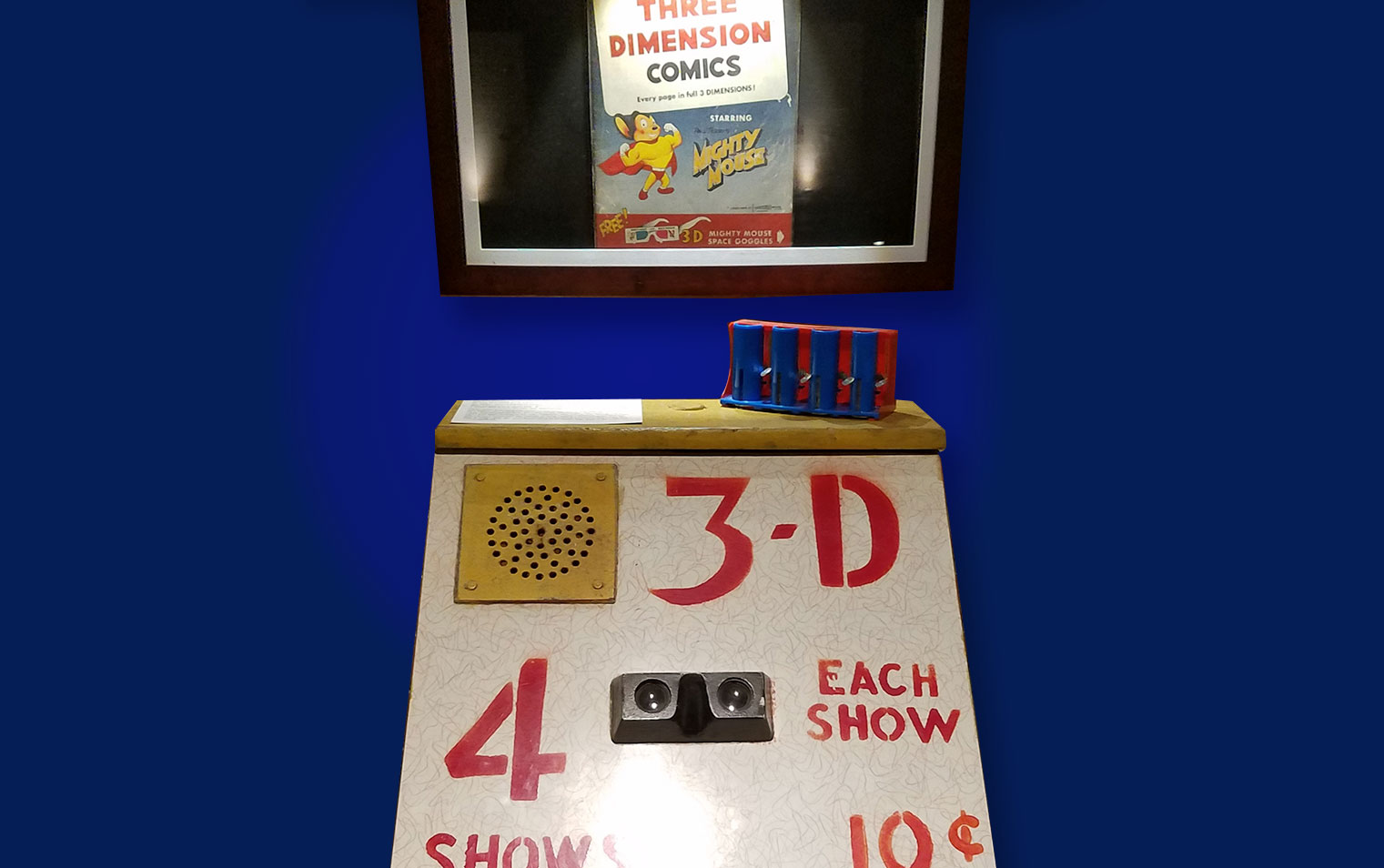

In 1838, British scientist Charles Wheatstone created a table-sized device to prove his theory: If you draw two images from two marginally different perspectives, and then view each image through a different eye, your brain will naturally see them in three dimensions. His invention was the world’s first stereoscope. From there, 3-D became a staple of entertainment: Mathew Brady took 3-D photos of Lincoln, and practically every Victorian home had a hand-held stereoscope. The first 3-D movie was test-screened in New York in 1915. 3-D then went through a golden age of film, comics, and photography in the 1950s . . . and then Avatar was released.

OK, I skipped a lot, but this is why you need to visit 3-D Space yourself. My version of stereoscopic history falls flat, while Eric’s teems with depth, humor, and passion — and comes alongside superbly curated screenings, restoration campaigns, and exhibits. For example, his current show “Not Just a Kid’s Toy: The View-Master,” illustrates that the world’s love of hand-held stereoscopes never died; it just shape-shifted. He displays the evolution of View-Masters — from prototype to latest incarnation — as well as the actual 3-D models sculpted and photographed by the artists responsible for popular Flintstones and Disney-inspired reels.

View-Masters on display for the Not Just a Kid's Toy exhibition

Instead, I’ll stick to talking about how 3-D Space itself came to be because it’s a quicker story, one rooted in Hollywood history, the LA underground comics scene, Nashville hot chicken, and serendipity.

In the zone

About ten years ago, Kurland’s personal experiments with 3-D eased him out of a career in studio animation and into doing several 3-D music videos for the power pop band (and viral video phenoms) OK Go, one of which was nominated for a Grammy. He also held the role of lead stereographer for the Oscar-nominated short Maggie Simpson in “The Longest Daycare” (2012).

Around this time, he joined the LA 3-D Club, a gathering of enthusiasts that have met monthly since the 1950s, when people like Harold Lloyd, Moe Howard, and Vivian Leigh were all avid stereoscopic photographers. It was here that Kurland met his mentor, Ray Zone, “The 3-D King of Hollywood.”

In the 1980s, Zone co-owned a gallery in Silverlake called Zomo and hosted “The Zone Show” on public access TV, which featured interviews with musicians and artists, including Marvel universe co-creator Jack Kirby. He wrote several books on stereoscopic cinema and, most notably, adapted more than 150 comics and graphic novels to 3-D throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

In 2012, Kurland and Zone went to the estate sale of Dan “Mr. 3-D” Symmes, a former X-rated film director and fellow 3-D enthusiast. Zone left almost upon arrival because he was too pained to see how Symmes’ vintage stereoscopic equipment was being handled.

Kurland, however, stuck it out and was introduced to “Uncle George,” who respected Kurland’s interest and asked him if he’d ever heard of his old friend Ray Zone. Kurland realized immediately that he was talking to George DiCaprio, who used to publish comics with Zone back when Zone lived around the corner from DiCaprio and his son Leonardo. He promptly called Zone and had him return to the sale. After purchasing several truckloads of Symme’s collection, DiCaprio made them promise they’d do something with Symme’s material. That’s when Zone and Kurland began to speculate about starting a 3-D museum.

A few months later, Zone unexpectedly died of a heart attack, and Kurland once again found himself rescuing a beloved trove of stereoscopic equipment. He purchased a good chunk of Zone’s collection from his son, Johnny Ray. As Kurland puts it, “I kind of feel like I subsidized his son’s restaurant. Have you been to Howlin’ Ray’s?” He meant that Howlin’ Ray’s, the Nashville hot chicken sensation in L.A.’s Chinatown famous for its comeback sauce and four-hour lines. Johnny Ray named it after his father.

A vision emerges

With two solid collections now tucked away in his Echo Park storage space and the notion of opening a museum swirling in his mind, things began to fall in place for Kurland. The recently closed Portland, Oregon-based 3-D Center for Art and Photography offered up its collection if he could register as a nonprofit, which he did in 2015. Then, in 2017, his landlord asked him for advice on what he could do with a basement storage area he’d recently cleared out. Kurland rented it, and 3-D Space officially opened its doors in the summer of 2018.

Kurland said the reception to the museum has been nothing but positive. He’s assembled an impressive advisory board that boasts Queen guitarist, astrophysicist, and author of several books on stereoscopic photography Brian May and has already held several exhibits, festivals, workshops, and screenings. He envisions eventually moving into a larger space with permanent exhibits and more resources for people interested in creating their own stereoscopic art.

“Ray Zone always said there were two kinds of people in the world of 3-D,” says Kurland. “There are the magicians, and 3-D is their ‘secret sauce.’ They don’t share their secrets with anyone. Then there are the 3-D evangelists, who just want everyone to see 3-D. He always hoped I was the latter. That’s what I’m trying to do here with 3-D Space.”