Table of Contents

In March, 2020, as COVID-19 hit, most game industry employees were sent home from the office. Companies scrambled to compensate for the loss of their central office spaces where workers could interact, ideate, and create together.

As the pandemic begins to diminish, it's become clear that many workers - and even some employers - appreciate the benefits of working from home (WFH), while at the same time, still grappling with its challenges. A core challenge is the ability to maintain the culture and productivity altered by a remote or hybrid workforce.

Tools that seek to bridge physical and temporal distances between workers make remote work possible. But they also bring their own problems. According to Asana's recent Anatomy of Work report, 60 percent of a person’s time at work is spent on "work about work" and not on skilled work. In other words, people are spending huge amounts of time on communications apps that don't directly contribute to the worker's actual function.

The report found that the average knowledge worker spends "103 hours in unnecessary meetings, 209 hours on duplicative work, and 352 hours talking about work."

The games companies we spoke to invariably reported the same issues, with a tension growing between individual preferences for certain apps, how those apps were being used, and how much time and energy is going into unnecessary communications. Many reported confusion about which apps were best for the constant back-and-fro of creation and approval, as assets are shared, modified, and reshared.

In this report, we’ll dive into what the game industry has done to bridge this gap, some of the remaining issues leaders in the gaming industry face to balance productivity and culture, and tips on how to excel in the new hybrid world.

Disclaimer — We are grateful for the participation of the companies we spoke to, and their candid observations and insights. Their participation does not reflect any endorsement of MediaSilo.

Introduction

The game industry's technical prowess and culture of innovation proved to be advantageous when the world faced lockdowns and other consequences of the pandemic. Mainly staffed by computer-sophisticates, game companies were able to continue their operations.

But video game companies also found many unexpected problems during COVID, often rooted in the game business's cultural history, as well as the unique nature of video games as extremely complex artifacts of creation. A rising consumer demand for video game entertainment during the pandemic added pressure to unexpected pain points, as game companies failed to hit milestone targets, and release dates were shifted out of the most lucrative times of the year.

Gaming's Cultural Singularity

All industries, including creative industries, were forced to cope with lockdowns. Many are now working their way into a future in which many workers are likely to opt for WFH, rather than attending an office every day, if practical and if offered the opportunity.

So why do the experiences of game companies differ from other similar businesses in the entertainment industry?

While it is certainly true that some games in the early years were made by individuals working from home, gaming's creative culture rapidly morphed into an intensely in-person collaborative endeavor. In fact, game creation and promotion has traditionally relied heavily on multiple in-person teamwork.

Most game companies - whether developers, publishers or service providers - are formed by small teams of friends or colleagues who work closely together, constantly sharing each other's work. Over-the-shoulder collaboration is central to how games are made.

When you read about the early days of a successful games company, the founders will almost always speak about how much time they spent together, bouncing ideas off one another, and critiquing each other's work. They will invariably credit this approach to their success. Invariably, they seek to scale this dynamic as their employee base grows.

Any part of a game can be changed at any time during its development, right up to the game's release, and even beyond (in the form of additional content, patches, modes etc). These alterations might range from a tiny, single sound effect, to the entirety of the lead character, to the very nature of the game itself. Sometimes, alterations can be made after feedback from early reviews to ensure the game delivers against massive expectations.

Venture capitalist Matthew Ball recently noted how much more content games companies offer compared with competitors in other entertainment industries. "Video games are a platform for multiplayer storytelling, rather than a linear narrative. Fortnite has only marginal changes each multi-month season, but the reliance on 'your friends' and unscripted narratives means that a player can spend dozens of hours satisfied. The Office is highly rewatchable, but over its nine-year run, it produced less than 75 hours of unique content. Game of Thrones ran for eight years and produced the same. "

Late in their creation, mystery novels do not suddenly become comedies. Movies that make drastic late changes are assumed to be suffering from creative challenges, and expectations for commercial success are downgraded accordingly. But in games, radical and constant iteration is necessary to the process, and is viewed as financially advantageous.

Games are tactile. Their creators must touch them, in much the same way that a chef tastes a new dish.

Big changes must also be reflected in a game's marketing, as emphases move from one innovation to another.

Games are tactile. Their creators must touch them, in much the same way that a chef tastes a new dish. Games are complicated amalgamations of processes and assets. But each ingredient can only be added by a specialist. All the other specialists are expected to ensure that any change works with their particular ingredient to the advantage of the whole. One change must necessarily lead to many other alterations.

In game development, iterations are a constant, and involve the agreement and participation of different people. From producers to gameplay designers, to artists and writers, to musicians and programmers, down to testers, this is often done in the moment, collaboratively.

Limitations of generic communications tools

Matt Casamassina is CEO of Rogue Games, a California-based publisher which employs around 20 people, most of whom he speaks to on a daily basis. His normal office routine is to do the rounds and check in on his team members, discussing the wide variety of development clients that the company handles. But when lockdown hit, he found himself having to use Slack as his primary conduit between himself and his staff.

While Slack is a useful tool, it is not a substitute for in-person communication. Many of the companies we spoke to said that its usefulness can be undermined when multiple channels are being created without much oversight, nested within one another, making navigation problematic.

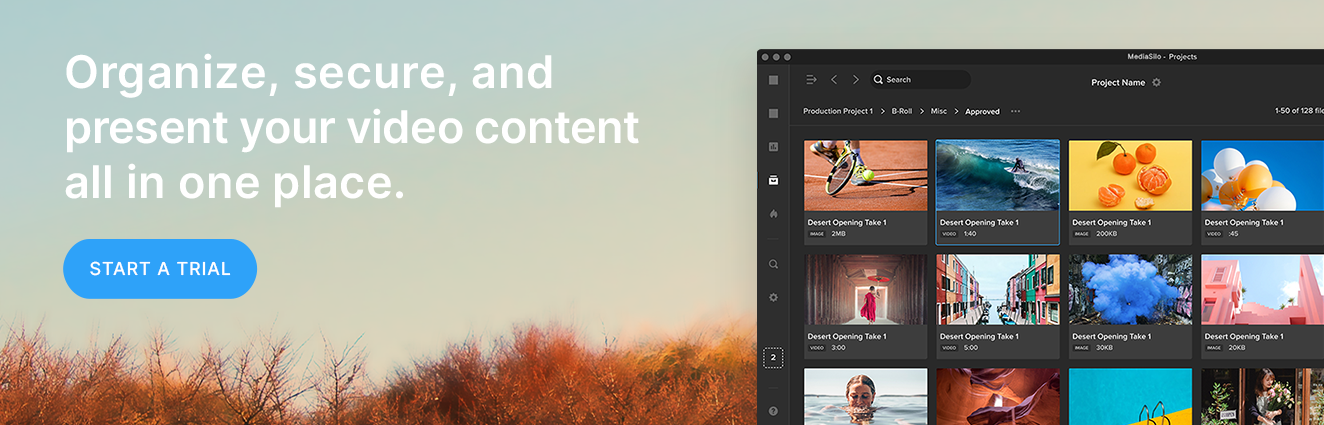

Interested in seeing MediaSilo in action? Contact us to get started on a free 14-day trial today.

It is best understood as an asynchronous conversation. Casamassina learned this after fellow team members gently suggested to him that he was trying to use it as a live-chat device, and that he was too impatient and insistent for immediate responses.

"When you're at home, sending an email or a slack out into the digital ether, I want a response right away. But sometimes I might not hear back for hours and I start to wonder, 'hey, where's my response?'.

"I learned that's not good behavior from a leader. I'd worked in offices for a long time, and I was programmed for that environment. But those expectations don't fit when you're remote. I really had to address something that came across as me being unreasonable, while making sure that our workflow improved.

"So we talked with the team about how to create optimal communication practices, without too much rigidity. We put practices in place that allowed me to loosen up and unlearn those bad habits that I had to really grow out of. At the same time employees stepped up. We built a system together that everyone understands, and that has helped our workflow and our culture."

Most of the companies we spoke to reported that their Slack usage has become more sophisticated and organized since lockdown, with a larger number of channels, generally serving hyper-specific purposes.

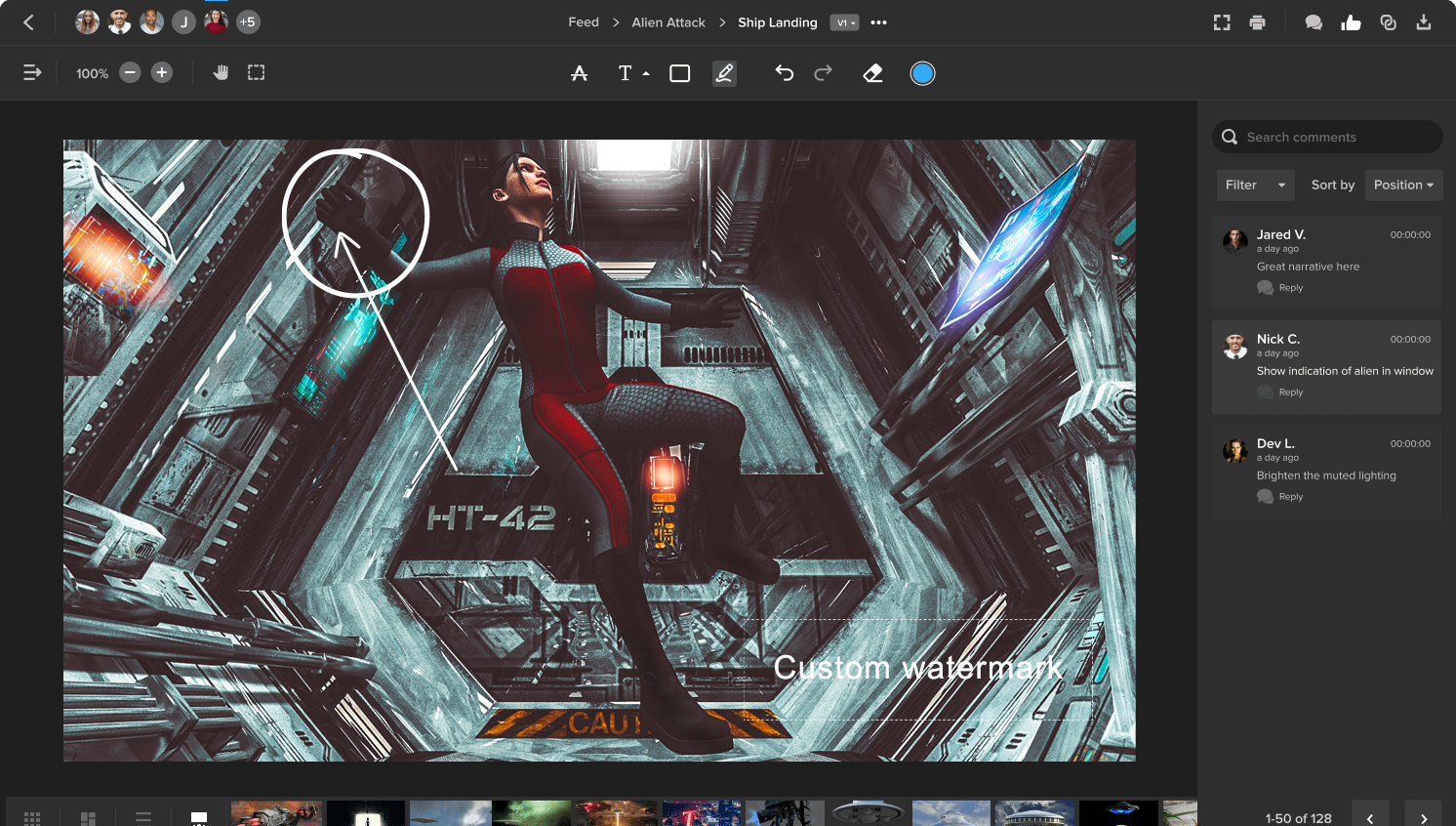

The future of feedback, approvals, and comments is likely to move away from generic solutions like Slack toward specific tools, like MediaSilo, which allows for on-screen annotations, frame-accurate comments, and one-click approvals for video and animated assets.

Most industries now make regular use of video meeting tools like Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, and Skype, and Discord to gather ad hoc input throughout the creative process according to a company's needs.

"I might sometimes be in a [virtual] meeting and I'll take a screencap from Discord and transfer it into Slack," said one. "We're mixing and matching according to the needs of the moment."

Zhenghua "Z" Yang is founder of Serenity Forge, a Colorado-based developer and publisher. "Our Discord server is a digital office space," he explained. "Each person on our team has their own voice channel and when you're working, it's assumed that you're on your channel, but if you're not, that's okay, it's just like someone not being at their desk because they went out to get a sandwich or something.

"You can mute Discord, but if you're there, anyone can pop into your channel and say 'hey, what's up … you know like … did you finish that one thing?' And Kevin can quickly unmute and say 'oh yeah I just finished it', and then 'okay, all right, cool. I'll see you later'.

While these collaboration tools fill in some of the gaps, they are not without issues. Different functional teams have different needs and levels of adoption for collaboration tools, leading to a disjointed collaborative workflow.

"I might sometimes be in a [virtual] meeting and I'll take a screencap from Discord and transfer it into Slack," said one. "We're mixing and matching according to the needs of the moment."

Security Protocol Changes

Game companies are notoriously secretive, and for good reason. Releases are highly visible, competition is fierce, ideas are premium, and assets are valuable. Partnerships rely on discretion. Most of the companies we spoke to talked about how they invested a great deal of time and energy into making sure their security was able to withstand entire teams suddenly logging in from home. For some, it took months to get to a situation where they felt comfortable.

Christina Seelye is founder and CEO of California-based publisher Maximum Games, which employs around 50 people. "Making sure that everyone can get into the VPN [Virtual Private Network] properly was an early priority," she said. "Cybersecurity issues are really important for us. When people are working from home, they all have their own challenges, and it's essential to talk those over, individually.

MediaSilo works with some of the most sensitive pre-release content on Earth, so security is paramount. We emphasize security from content protection to protecting our client’s Personal Identifiable Information.

"Sometimes it's just little stuff like people who might let their kids play on the computer, or who have roommates. What is the right thing to do when you're in a Zoom call and talking about something that isn't publicly disclosed? So we had to make sure that we were being really careful about understanding that confidentiality and security practices, which work fine in the office, work differently at home. Security has become a major priority over the past year."

MediaSilo security director, Simon Lamprell, believes that security is crucial internally and externally. “We work with some of the most sensitive pre-release content on Earth, so security is paramount. We emphasize security from content protection to protecting our client’s Personal Identifiable Information (PII). Also, whenever we engage with a new vendor or third party we perform a full security assessment and review their protocols and practices around PII to ensure they meet our security standards.”

Protect and Share the Build

Part of game company security is managing the latest build, or version of a game, or of the various assets that make up the game. Allowing employees to access the most recent version of the game means they need very fast internet connections, while the company must ensure that the build is both easily accessible by the right people and protected from the wrong people.

Many companies use their own servers, or version-control cloud depository services like Perforce. Some use online retail portals like Steam, where they can upload new builds every day which are easily downloaded by team-members. Many use a combination of resources that make sure that every version of the build is protected.

"As a producer I can look at all the graphs and all the data points in the world, but the real progress is the game itself," said Kerry Whalen, production manager at Piranha Games, which is best known for its Mechwarrior action games.

"We spend a lot of our time looking at the game and playing the game and talking about the version of the game that we're working with. When lockdown hit, we tried to [play the game] via remote desktop, but that's no good if you're at home with a laptop on the kitchen table and a terrible internet connection.

"So we resolved that problem by putting our games on Steam. We set up all kinds of different beta branches and delivery systems so people can access anything securely, play it, and give their feedback."

Control Meeting Madness

When they were forced into social separation, many companies overcompensated by instigating too many video meetings. Partly, this was driven by a well-meaning anxiety that employees might not be coping with isolation. Another reason cited by interviewees was a concern that, outside the milieu of the office, people might not all be on the same page. Information gaps might start to appear, hampering progress.

"We believe in the creative energy and the synergy of being physically together," said EA Motive's Patrik Klaus. "When we're apart, we message each other when it's needed. We've come a long way in getting better at that, but it remains a challenge to find the right cadence of meetings. Having a tool like Zoom is awesome, but Zoom fatigue is a real thing."

Having a tool like Zoom is awesome, but Zoom fatigue is a real thing.

Zach Truscott at ArenaNet said: "We're very used to having hallway conversations in the office, instead of meetings. But when you're remote, they're gone. So we set up meetings instead, and what we found is we went from a moderate amount of meetings to so many meetings that nobody was getting any work done. We were overbooking ourselves with meetings."

Truscott said that the company is resolving the problem by creating working pods which have a responsibility to keep stakeholders informed, while minimizing the amount of time spent in meetings. This is leading to more efficient means of noting and disseminating action points.

"Communication is an important part of game development," said Farah Coculuzzi, producer at Capy Games, a Canadian developer, currently enjoying success with mobile hit Grindstone. "We want to make sure that everyone has the capacity to do what they need to do [for work] and also to take care of their home life."

"A big thing for us is the realization that stand-ups don't always have to be at the same time every day. A few days of the week they're in the mornings and a few days they're in the afternoons. If someone regularly misses one or two because of other commitments, that's just part of how we do things."

Respect Camera Anxiety

On-screen meetings are now a normal part of office life, but some people dislike being on camera. This can cause friction between managers who want to literally see how their people are doing, and employees who are either naturally shy, or who wish to protect their own privacy.

Joel Burgees at Capy Games said: "One of the great things about Capy is we don't have a lot of braggadocio and peacock energy in the studio. But we do have some really soft-spoken folks on the team who are introverted. They are mega-talented, big-brains-big-hearts types of people and it's very rare that they will put their cameras on [during meetings].

"The people who are comfortable having their cameras on are more likely to be social and outgoing and it's very easy to hear their ideas because they are broadcasting it.

I have to give people space to be heard, especially if they don't want to be seen.

I have to be more proactive about making sure that the quiet people whose faces we can't see are encouraged to speak, without feeling like they have to turn on their camera. I have to give people space to be heard, especially if they don't want to be seen."

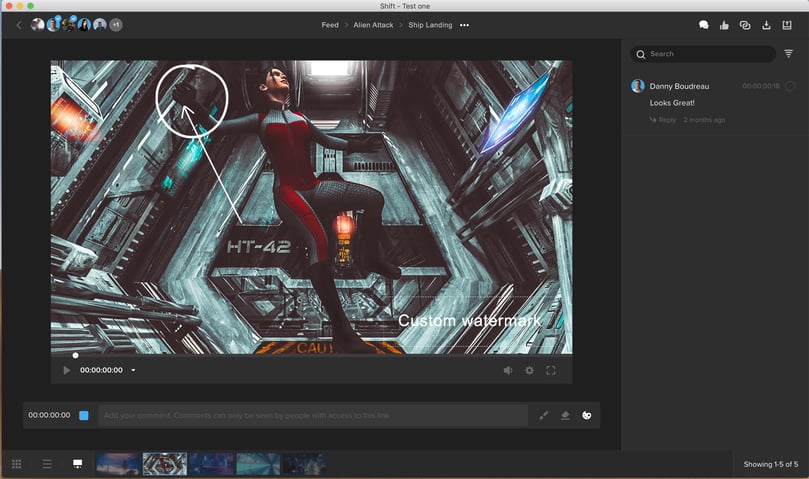

Respecting each employee’s camera sensitivities while still wanting and respecting their feedback during creative sessions is something that can be solved asynchronously through shared collaboration platforms.

-2.png?width=2492&name=image%20(2)-2.png)

MediaSilo provides a simple review and approval process letting stakeholders provide feedback without the hustle and anxiety of live, camera-on sessions.

Meeting in the Middle

A constant refrain from our interviews was the sense that the last 18 months have been a sharp learning curve for everyone, and that business leaders were no more prepared for the shock of the pandemic than anyone else.

The lessons that have been learned did not come from managerial theorists, or from super-bosses, but from trial and error. Most important of all is that physical isolation has only intensified a growing sense in the game industry that companies that try to dictate policy to employees will likely find it difficult to maintain a healthy working culture, and will struggle to retain and to hire talent.

The lessons that have been learned did not come from managerial theorists, or from super-bosses, but from trial and error.

EA Motive's Patrick Klaus summed up this thinking: "Our evolution during this time has been relatively organic, and I think we've succeeded because it was always super important for us to be listening to our teams, and being flexible in our approach.

"The situation needed a bottom-up approach and not a top-down approach. We talked. We listened and we figured the best way forward by meeting in the middle. One of the biggest things that I've seen is just an intense level of collaboration and communication at all levels."

Electronic Arts employs more than 10,000 people around the world, while the Motive studio is around one hundred strong. Klaus said that this presents a challenge, but that a local approach is essential.

"We had some great support coming from the head office but we've also been empowered to make our own decisions and to create our own destiny in terms of how we do things. We have found guiding principles that are applied to the whole company but then there is a flexibility built in at a local level."

Conclusions

In some industries, WFH is leading to anxiety that workers might take advantage of the situation, and decrease their commitment to work. In a competitive, passionate, creative industry like gaming, that is not an issue.

Those leaders we spoke to who are looking forward to "getting back to the office" are all working on plans to allow employees to work from home for either part, or all of the week. Creativity is at its peak in a person-to-person setting and it's a simple fact that some people prefer to work in a social environment.

There is also a common notion that when a game is in its conceptual, brainstorming stage, stakeholders work better in-person. On the other hand, the specific productivity of content creation - art assets, programming, music, level design, trailers - can just as easily be done from home, if that's the worker's preference.

All that explains why gaming is likely to move to a hybrid model in the years ahead. How that happens will be a continuing evolution of best practices, and of useful tools.

Every interview in the report mentioned multiple tools that they were using more extensively when they were away from the office, than when they were in the office. Most of these are familiar to us all, such as Slack, Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Trello, Asana, and Google Docs. But there are plenty of other tools that are either especially suitable for the game industry, or are coming to the fore as particularly good for specific, essential tasks.

We at MediaSilo work with some of the biggest names in gaming to bring the power of visual feedback to life. MediaSilo brings together assets and minds for in-progress creative projects. For example, concept artists use MediaSilo as a place to manage and share files, and marketing teams collaborate and approve campaign assets on their way to promoting highly anticipated titles.

As evidenced in the feedback and insights provided throughout this report, bringing collaboration out of non-stop meetings and chat clients allows for a cleaner feedback loop where everyone can participate. Please contact us to see how MediaSilo can take your workflow to the next level.